Fixing cross-border payments: the essential steps

Improving cross-border payments has become a top agenda item of global policy makers. The G20 has made “enhancing cross-border payments” a priority in 2019, and it continues to be a priority for 2021 under the Italian G20 presidency. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) has launched an extensive roadmap last year, as well: “Faster, cheaper, more transparent and more inclusive cross-border payment services, including remittances, while maintaining their safety and security, would have widespread benefits for citizens and economies worldwide”. In fact, this October the FSB published measurable targets for addressing four key challenges in cross-border payments: cost, speed, access and transparency.

This blog post first illustrates why cross-border payments are by nature much more complex than domestic payments. Arguably the most important component in this context is the fact that cross-border payments typically require a conversion of one currency into another (a “foreign exchange” or “cross-currency” transaction) thus, the most important area for improvement is how cross-currency transactions are processed and settled. The second part of this blog outlines the measures that should be implemented. And finally, we point out that central bank policies in terms of access to reserve accounts and processing hours of their own payment systems will play an important role as to whether tangible progress can be achieved.

Payment Flows in Cross-Border Transactions

The CPMI (Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures), a standard setting body for financial market infrastructures, defines cross-border as a “payment in which the financial institutions of the payer and the payee are located in different jurisdictions”. This definition is rather vague and includes a broad set of payments. According to CPMI definition a euro payment from a bank in Germany to a bank in France is a cross-border payment. But such a payment can hardly be seen as complex and slow. In fact, it can be processed in real-time at very low costs through existing payment systems like Target2 or RT1.

The more complex and, at a global level, more relevant type of cross-border payment is a transaction which also includes the purchase of a foreign currency against the home currency by the payer. Usually, the payer first has to buy the currency it wants to transfer to a payee that is domiciled in a different country before it can make a transfer to a payee. This is, for instance, the case of a company in Germany (the payer) that has to make a payment in USD to a supplier (the payee) in the United States. Such a cross-border transaction is slow and costly as the payer first has to exchange euros into US dollars and then transfer US dollars to the payee.

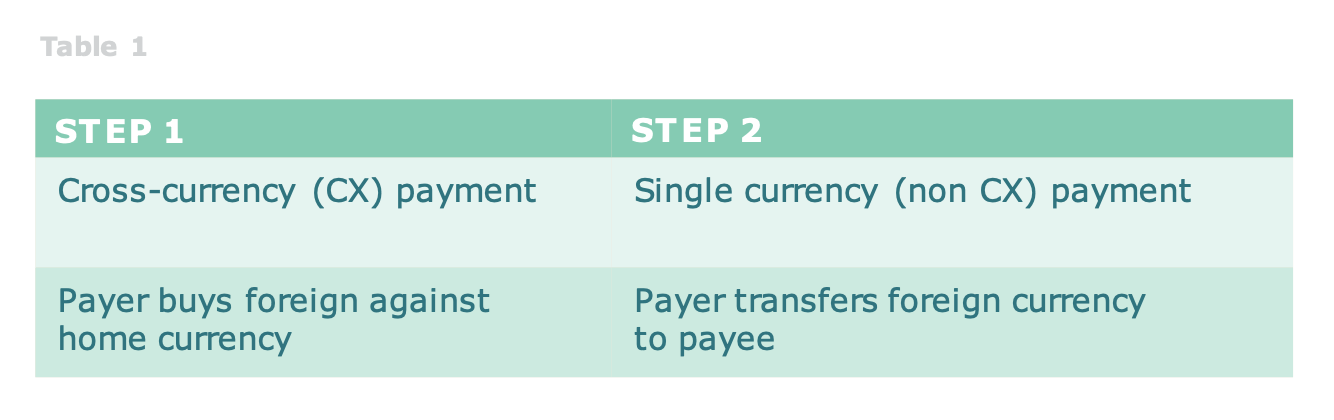

These two sequential steps in a cross-border payment are shown in Table 1: first, there is a cross-currency (CX) transaction in which the company in Germany (the payer) purchases US dollars against euros from a market participant. The second payment is a “normal” (non-CX) payment in US dollar from the payer (the company in Germany) to the payee (the US supplier).

For both steps the involvement of financial intermediaries is indispensable. While several options for the flow of money are possible, we focus here on a generic, stereotypical case. Also, we assume that all involved parties are “banked”, i.e. they have bank accounts and that the banks have direct access to correspondent banks abroad.[1] International remittances while also including a CX transaction are often processed through other channels and service providers. Also, not discussed here are cross-border transfers with crypto currencies.[2]

CX Payment Flows

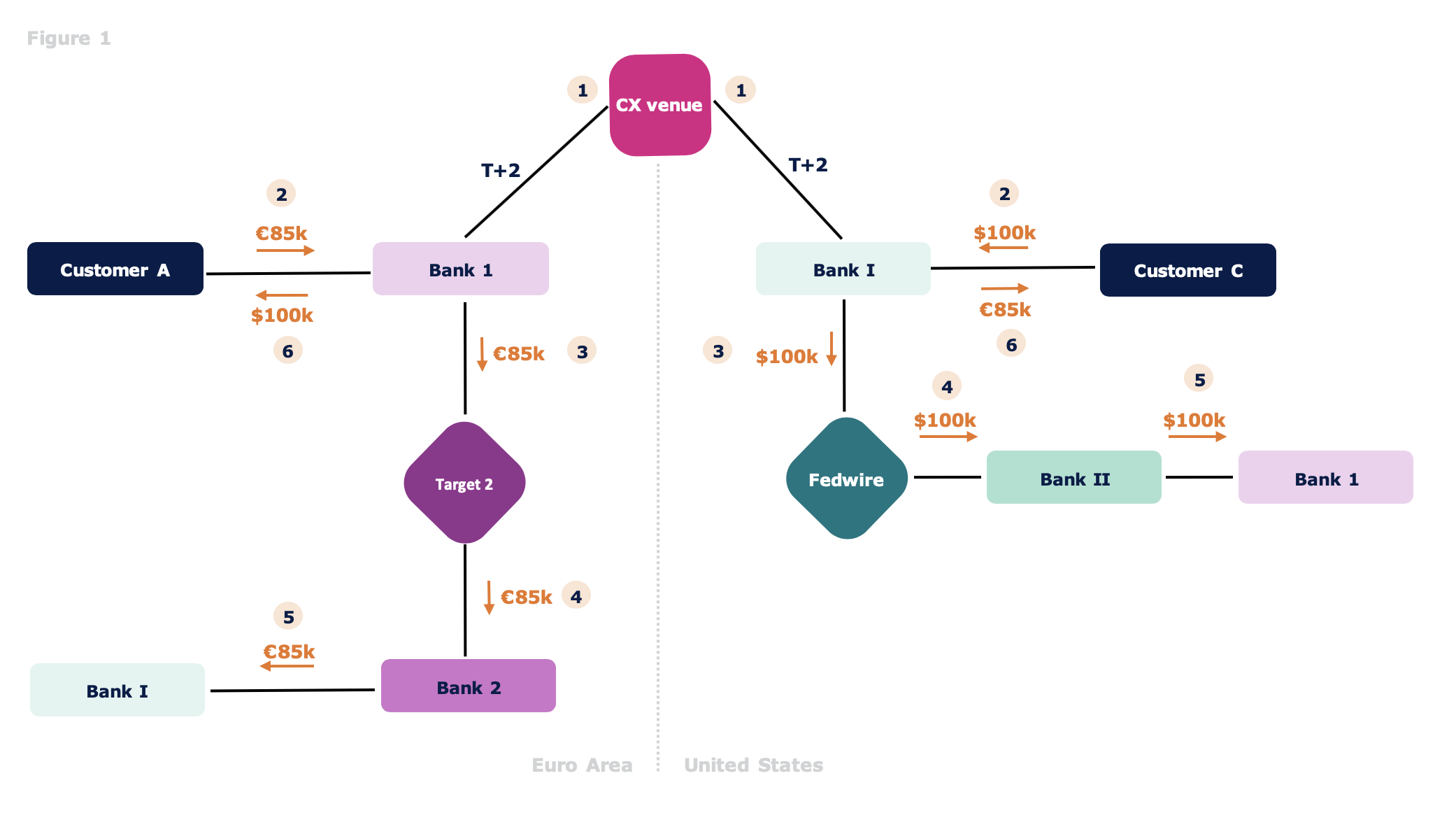

Let’s assume a payer in Germany (the payer; Customer A) has to pay a supplier in the United States (the payee; Customer B) USD 100,000 for an order. Figure 1 shows the various flows (in orange color) and entities involved. Customer A instructs its bank (Bank 1 located in the euro area) to make payment of USD 100,000 to a payee (Customer B). In order to affect this payment, Bank 1 will purchase USD 100,000 against EUR. Bank 1 submits an offer to buy USD 100,000 against EUR 85,000 to foreign exchange or cross-currency venue where the order is matched with an offsetting offer by Bank I (sale of USD 100,000 against EUR 85,000) which is domiciled in the United States. Bank I had submitted the order on behalf of one of its clients (Customer C). Customer C could be a professional CX trader. Alternatively, Bank 1 could just sell some of its own US dollars to its client (Customer A) at the market exchange rate plus a commission.

After trade execution the two counterparties to the transaction (Bank 1 in Germany and Bank I in the United States) specify when and through which payment systems the trade will be settled (“value day”). Usually, the value day of a cross-currency transaction is two days after trading (“T+2”). This is marked as step (1) in Figure 1.

On value day, the payer’s bank (Bank 1) transfers EUR 85,000 (and deducts it from the account if its Customer A) to Bank I, the counterparty to the CX transaction (steps (2) and (3) on left side of Figure 1). If Bank I has an account with a central bank of the eurosystem, the payment is made directly between Bank 1 and Bank I in Target2 (an interbank payment system operated by the European Central Bank). It is, however, more likely that Bank I doesn’t have an account at a central bank of the eurosystem. Then, the payment is made to its euro area correspondent bank (Bank 2). Bank 1 will send a payment instruction to Target 2 to transfer EUR 85,000 to Bank 2 indicating that Bank I is the ultimate beneficiary.

For the settlement of the USD leg of the CX transaction the process is analogous. On value day, Bank I debits the account of its Customer C for USD 100,000 (step (2) on right side of Figure 1) and then makes a payment of USD 100,000 in Fedwire (an interbank payment system operated by the Federal Reserve) to Bank 1 (if Bank 1 has an account at the Federal Reserve) or to its US correspondent bank (Bank II) with Bank 1 as ultimate beneficiary of the payment (steps (3) and (4) ). Once Bank 1 and Bank I see that they have received the expected amounts (USD 100,000 for Bank 1; EUR 85,000 for Bank I) they credit their customers (Customer A and Customer C; step 5).

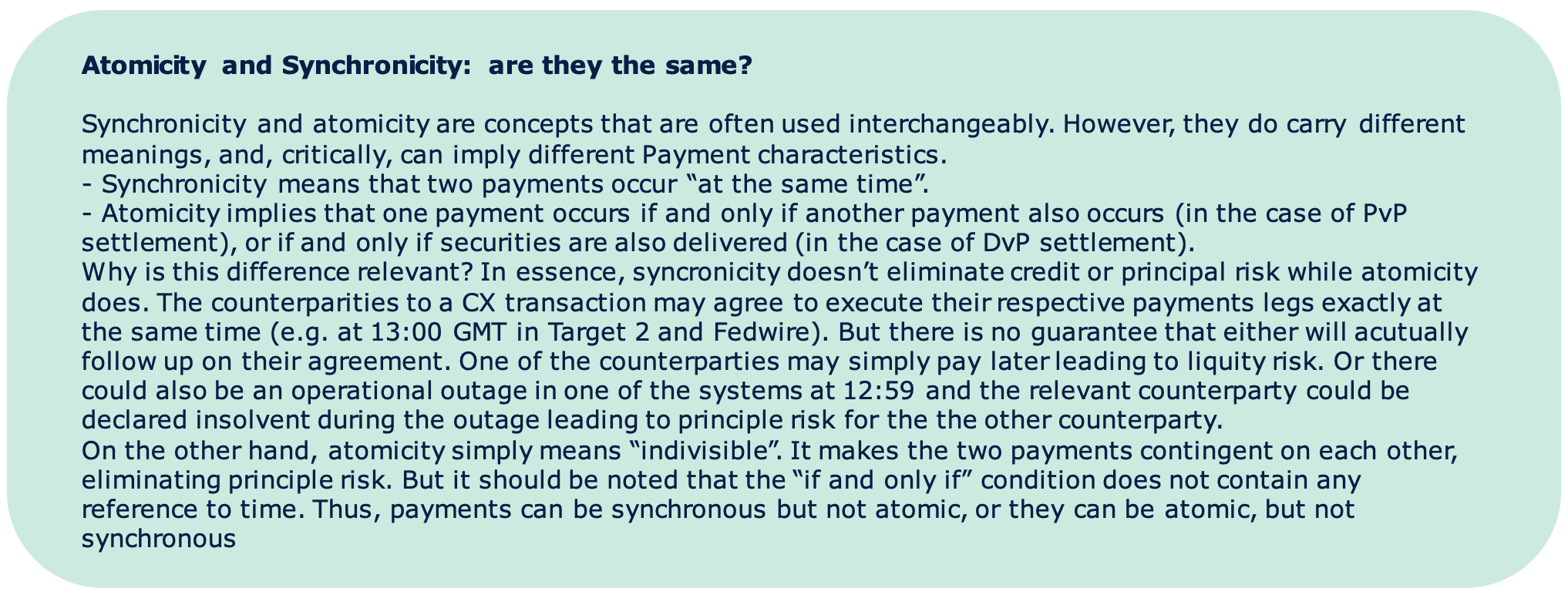

The settlement of CX transactions has historically been risky as the two legs of the transaction settle in two different payment systems (Target 2 and Fedwire in our example). On value day each counterparty has to transfer the amount it owes to the other without having certainty whether the counterparty will also pay its leg of the transaction. Put differently, the US dollar payment and the euro payment neither happen simultaneously nor are the contingent on each other. If the counterparty never pays (e.g. if it defaults on value day) this risk is referred to as principle or credit risk. If the counterparty pays with a delay (e.g. the day after value day), the risk is called liquidity risk.

A straightforward way of reducing credit risk in the settlement of CX transactions is to introduce a feature that makes the payment of both legs of the transaction (“payment versus payment” or “PvP” contingent on each other: one leg of the transaction settles if and only if the other leg also settles. In this context the difference between synchronicity and atomicity is relevant (see the box below). CLS Bank, for instance, is the currently the largest infrastructure to settle CX transactions on a PvP basis. Participating financial institutions hold accounts denominated in various currencies with CLS Bank. CLS provides PvP settlement for individual CX transactions on its book under the condition that certain settlement conditions are met. But despite CLS Bank, CX settlement risk is still enormous. Every day CX payments worth close to USD 9 trillion remain at risk (Bech and Holden (2019).

Non CX cross-border payments

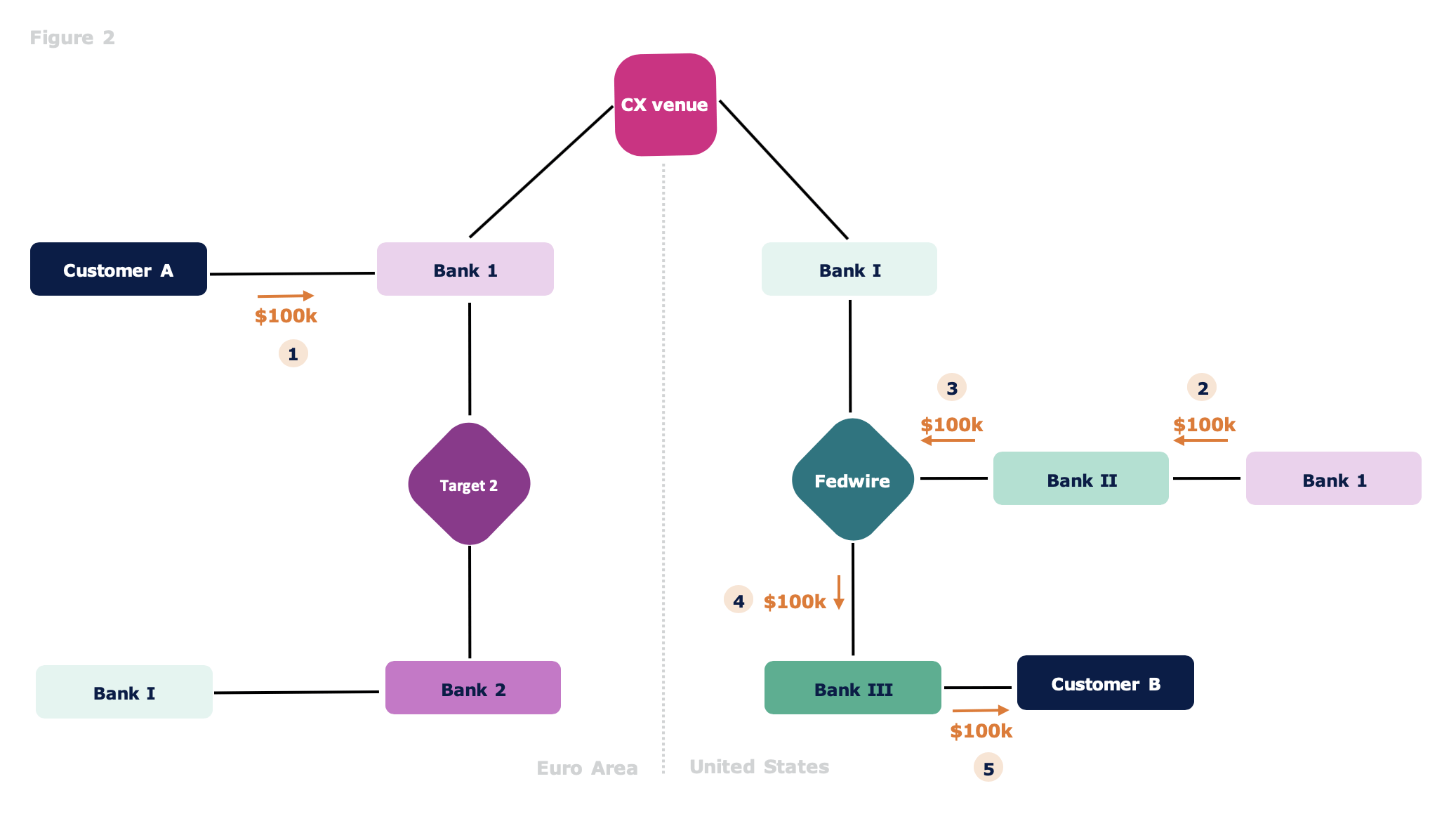

Once a payer has received the foreign currency it wants to transfer, the second step is a non-CX cross-border transaction. In our example this is the transfer of USD 100,000 from the German payer (Customer A) to a payee in the United States (Customer B). The payer holds USD 100,000 with its bank in Germany (Bank1) while the payee has an account with the Bank III in the United States. Upon instruction by its Customer A (step 1) in Figure 2), Bank 1 advises its correspondent bank in the United States (Bank II) to pay USD 100,000 to Bank III with the payee (Customer B) being the ultimate beneficiary (step 2). Typically, Bank 1 instructs its correspondent a day before the payment to the beneficiary is made. Once the correspondent bank (Bank II) has sent the transfer order to Fedwire (step 3), it usually settles immediately (step 4). Bank II then credits the account of its Customer B (step 5).

It should be noted that the example provided here is relatively simple. First, the correspondent banking chain may be longer since not every bank has a correspondent bank in every currency. This means that it will need to have an account arrangement with another domestic bank which has a correspondent bank in the foreign currency area. Second, bank clients may have a positive account balance in a foreign currency and make payments in that currency even if their bank doesn’t have a corresponding long position with its correspondent bank, i.e. the bank has a “currency mismatch” on its balance sheet. Then, in order to be able to make such a payment (and avoid overdraft charges with its correspondent) the bank needs to borrow the foreign currency at short notice, for instance, from the money market participants or its correspondent bank.

Remedies

Given the currently rather complex processes in cross-border payments as described above it is clear that there is no easy fix. Legacy systems and platforms cannot be “upgraded” overnight and rolling out new infrastructures is costly and time-consuming. In my view, three measures for improving cross-border payments stand out.

1. Increase of PvP settlement of CX transactions

As mentioned above credit or principal risk in the settlement of CX transactions is a major threat to financial stability. Thus, there is an obvious need for co-ordinated settlement of both legs of CX transactions (PvP or Payment versus Payment Settlement). Building block 9 “Facilitating the increased adoption of PvP” of the FSB Roadmap also emphasis this necessity.

There are essentially only two ways to achieve to make two payments contingent on each other. The first would be to directly link the two payment systems (like Target 2 and Fedwire).[3] With a such a direct link PvP can be achieved by first blocking (or “ear marking”) the amount in one system, for instance EUR 85,000 in the Target2 account of Bank 1. Once the funds are blocked a notification is sent to the other payment system (Fedwire). If Bank I has more than USD 100,000 in its Fedwire account, USD 100,000 are transferred to Bank 1 (or its correspondent bank (Bank II)) and the EUR 85,000 earmarked in Target 2 are paid out to Bank I or its correspondent bank (Bank 2)). To our knowledge no such direct links between payment systems exist so far enabling PvP settlement. The Fnality Global Payments Initiative , a consortium of leading global banks, is planning to deploy this approach to the settlement of cross-currency transaction in the major currencies using bilateral links between individual Fnality Payment Systems.

It is worth noting that such contingent settlement processes have been used in the settlement of securities transactions for a couple of decades.[4] The securities of the seller are earmarked first in the securities settlement system and the exchange of ownership of both cash and securities takes place simultaneously, if and only if the buyer of the securities has enough money in its account.

Another way to achieve PvP in the settlement of CX transactions is to have a central entity or platform which provides accounts in multiple currencies to participants in the cross-currency market. Such an approach has been used by CLS Bank for two decades. It also appears to be pursued by some central banks and monetary authorities in the project Inthanon-LionRock. Settlement takes place at the central entity if both counterparties (or their designated correspondent banks) are holding sufficient funds in the currencies they sold in a CX transaction.

2. Shorter settlement lags

Today, CX transactions are typically settled two days after the trade has been made (trades are “post-funded”). This leads to the risk that in case of default of one of the counterparties during these two days, the surviving counterparty has to replace the original trade at possibly worse conditions (“replacement cost risk”). Thus, the shorter the settlement lag the lower the replacement cost risk. At the extreme, if trade and settlement take place at the same time (instant settlement), replacement cost risk would disappear entirely. This would, however, require pre-funding of trades. This would likely entail a number of operational and behavioural adjustments for market participants.

The reason for the two-day settlement lag is largely operational. Correspondent banks currently batch-process transactions at the end of the trading day. These processes mean that the transactions can be aggregated and then require additional allow for the net funding to be acquired. A case in point is CX settlement through CLS Bank. CX transactions of thousands of financial market participants are funded by only a few correspondent banks (“settlement members”) in each currency.

The Fnality Global Payments Initiative will offer its participants flexible options as to when they want to settle their CX transactions. For certain CX trades – like urgent short-term liquidity operations – they can opt for same-day settlement or even (near) instant settlement. For less urgent CX trades they can continue to use T+2 settlement. Fnality is able to accommodate very short settlement lags in major currencies thanks to 24/7 operations and a peer-to-peer (non-intermediated) settlement paradigm. The benefits of the latter are discussed in the next section.

3. Reduction of intermediation and tiering

As shown above in the stylised cross-border transaction the settlement of both of its components (the CX payment and the non-CX payment) are likely to be intermediated by the reliance on correspondent banks. Not only do long transaction chains lead to high costs and credit and operational risks, they also imply that it may take several days to complete a cross-border payment: e.g. 2 days to receive the foreign currency and then one day for the transfer of the funds to the payee.

A promising way to shrink the transaction chain would be a direct (i.e. non- intermediated) involvement of financial institutions in the CX settlement processes, both domestically and abroad. This can be achieved by enlarging direct participation in a payment system and enabling financial institutions to manage their payment flows also in foreign currency themselves. In the Fnality Global Payments ecosystem, direct access of financial institutions to any of the Fnality Payment Systems is a foundational principle reducing tiering and the importance of correspondent banking networks. The importance of broader access is also recognised by Building Block 10 “Improve (direct) access to payment systems” of the FSB Agenda.

Role of central banks

Central banks are an essential factor in eventually making the G20 cross-border payments agenda a success. Two policy changes are particularly relevant in this context. They would remove important obstacles to making cross-border payments faster, safer, cheaper, and more efficient.

Central banks should evolve their account policies to enable broader access (Building Block 10 of the FBS Agenda) with a view of having less intermediated cross-border settlement processes. On the one hand, they should provide omnibus (or equivalent) accounts to regulated and overseen payment systems. On the other hand, these payment systems should be allowed to provide direct (non-tiered) access to a wide range of supervised financial institutions. If deemed necessary from a monetary policy or financial stability point of view, constraints on certain direct participants can be imposed, e.g. caps on end-of-day holdings.

Central banks should also extend the operating hours of their large value payment systems to nearly 24 hours per day (Building Block 12 of the FSB Agenda). Notwithstanding notable exceptions like the Federal Reserve or the Swiss National Bank, many central bank-operated interbank payment systems are still closed at nighttime, often between 6 pm and 7 am. In a payments world that has moved to 24/7 settlement, these restricted operating hours seem rather antiquated. During central bank off hours, precious highest quality money sits idle and cannot be used to fund settlement accounts in other connected payment systems. This leads to fragmentation of liquidity, unnecessary costs and settlement delays.

[1] In reality, not all domestic banks have a correspondent bank abroad. They will have to use another domestic bank which has a correspondent banking arrangement to make a foreign currency payment.

[2] Cross-border payments with cryptocurrencies typically involve two CX payments and one non-CX payment. First, the payer purchases crypto-currency against her home fiat currency; then the crypto-currency is transferred to the payee; and ultimately the payee sells the crypto-currency against her home currency.

[3] It is worth noting that central banks could have provided PvP settlement services by linking their RTGS systems for a long time. In this respect, there is no need to develop CBDC schemes first and then link them to achieve synchronised settlement of CX transactions.

[4] The standard-setting bodies CPMI and IOSCO refer to this settlement process as DVP (delivery versus payment) Model 1.

Photo by Andreas Brücker on Unsplash