Are Stablecoins a threat to Capital Markets Incumbents?

At the start of this year, I wrote a post speculating that 2021 may be the year of dFMI. Happily, there has been some significant progress on this front, such as the creation of an Omnibus Account Structure by the Bank of England and a clarification of the usage of ECB technical accounts paving the way for pre-funded payment systems. However, nearly three quarters of the way through the year, I admit I may have missed an important stage of evolution: the speed of stablecoin acceptance!

While the hype around stablecoins has been ongoing for some time, their prominence has amplified this year with the top five stablecoins having reached a market cap of around 100 billion USD. Interest in stablecoins has reached such a pitch that even the US Treasury has convened the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets to issue recommendations on potential benefits and risks, and to address legislative and regulatory gaps.

There isn’t a widely accepted legal or regulatory definition of stablecoin currently. This makes discussions on the topic somewhat difficult. For the purposes of this post, I consider stablecoins to be a class of cryptocurrency offering stability against some type of reserve currency or assets utilising Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT). It seems rather unusual to label financial products and instruments according to the technology they use for record keeping, but that appears to be part of the current understanding of the term.

Most of the usage of stablecoins is currently focused on a single use case: providing a settlement asset that matches the speed and efficiency of cryptocurrency trading. Stablecoins allow cryptocurrency traders to efficiently buy and sell cryptocurrencies without the need for the plethora of intermediaries currently found in mainstream capital markets. This basic use case has been leveraged to create a type of deposit taking industry that is known as yield farming, but could easily be called “banking”! As noted in wikipedia,

“A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.”

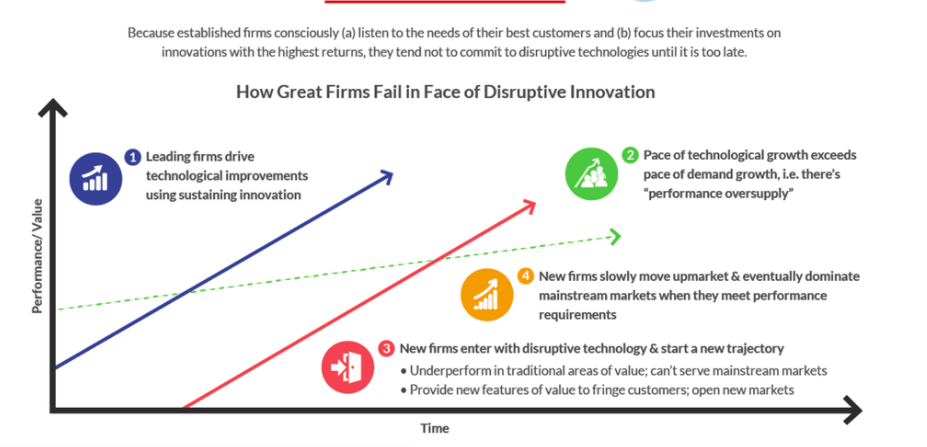

For some of you familiar with disruption theory, this incursion into a new market using new technologies and methods will have a familiar feel to it. The introduction of stablecoins for the use case described earlier seems to be the initial stages of the disruption process famously laid out by the late Clayton Christensen. In his ground-breaking book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Christensen describes the process by which incumbents lose their positions of leadership within their industry. The theory explains how the downfall of leading or incumbent firms occurs precisely because the incumbents are making good decisions based on exactly what their customers want!

In a nutshell, incumbent firms focus on “sustaining innovations” which improve existing products, like adding more and more blades to razors. Incumbents also tend to focus on the high margin end of the market over time as these customers are generally more profitable. The need to maintain customer satisfaction and profits keeps incumbents trapped on this path. Disruptors cannot compete directly with incumbents in the high end, but they often find new business methods that allow them to compete at the low end or to find new markets that need to satisfy the same product outcomes. While these methods initially result in products that are inferior to those available in the high end, eventually, these low-end products or new market innovations allow the disruptors to incrementally improve their products or services and move up the consumer segment curve until they eventually overturn the incumbents. The following diagram shows the process:

Credit: https://foundry4.com/at-a-glance-the-innovators-dilemma

Dollar Shave Club is a good example of this; the old model of “improving” razor technology could not be penetrated by Dollar Shave Club. The innovation was to realise that some consumers were already satisfied with the quality of their shaves and would gain much more utility from the convenience of easy order and delivery service.

Stablecoins used as a settlement asset for cryptocurrency trading could be considered a new market. Could it follow the classic Innovator’s Dilemma path? Here is a possible scenario:

Stage 1: Stablecoins continue to generate revenues in facilitating crypto trading, but become regulated to ensure their survival and spur confidence in Defi.

Stage 2: Having been successful at crypto trading, (younger) investors want to have the perceived convenience and independence of crypto trading and DeFi generally brought to other assets. New blockchain based CSDs and Securities Settlement Systems spring up to meet this demand, using stablecoins as the settlement assets.

Stage 3: Transaction costs are so low on these new decentralised platforms that smaller Asset Managers start to take advantage. Risks are removed and back-office sizes reduced. Incumbents don’t worry about these accounts as they were not highly profitable.

Stage 4: Stablecoin arrangers are able to gain more and more trust and improve the transparency on the backing of their arrangements.

Stage 5: Larger financial institutions realise that they can use the benefits of these services to offer much more engaging products to their clients with real-time risk and balance sheet updates possible. The lowering of risk and cost are also very compelling. They start to peel away from incumbents.

Stage 6: Incumbents launch their own stablecoins, but they struggle to gain traction as they try to cannibalise their own businesses and their customers rebel against a sea of stablecoins that re-introduce significant inefficiency. In the arena of Financial Market Infrastructure, the story of SWIFT, which competed against other incumbent proposals, shows the difficulty and single incumbent would have in persuading other players to adopt a single company solution.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Let’s start with the Christensen theory. Apple and Uber are classic examples of how disruption has happened at the top end of the market. Apple’s strategy has been to innovate at the high-quality end of the market and then use those innovations to drive further into lower segments. Uber also started by only allowing users to hail black luxury SUV’s at 1.5 times the cost of a taxi! The lesson here is that, given the right conditions, it might be possible to escape the innovators dilemma and the top end of the market. Other commentators, such as Harvard historian Jill Lepore, have also suggested that the theory, while elegant, has no predictive power and only explains the things it explains!

An important pre-requisite for stablecoins to become suitable settlement assets for capital market transactions is their full compliance with all regulatory requirements. While regulators around the world are still contemplating how to regulate stablecoin arrangements, it is clear that obtaining regulatory approval will be a tall order to fill.

Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that almost all innovations in the wholesale payments space have come from consortia of incumbents. SWIFT, EBA Clearing, CHIPS, Faster Payments all originated as bank consortia. In fact, the only rivals to these types of private sector systems, once established, come from the Central Banks themselves with their RTGS and, more recently, their instant payment initiatives. To some extent, we see the interest in CBDCs as a repeat of this history; a history where there is a co-existence of a limited number of private sector systems and competition from public sector systems.

Fifteen leading financial institutions have come together to create Fnality as an industry answer to the question of how to create a payment leg that facilitates the innovations of the cryptocurrency space in regulated financial markets. Fnality has spent several years uncovering the path to regulatory compliance, the key to which has been understanding how existing laws and regulations can be applied to a payment system based on DLT. In a nutshell, Fnality is creating a set of regulated payment systems, a pre-existing category of arrangement, which have a defined set of regulatory principles (the CPMI-IOSCO Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures or PFMI) already. Fnality is an innovation designed for the most sophisticated and demanding consumers; it is aiming at the high end.

So will the incumbents in capital markets rise to the challenge? Some already have! All the hallmarks of the innovator’s dilemma are present, but the establishment of Fnality provides a way out.

Photo by Tech Daily on Unsplash